Diary December 2016

- bluebirdk7

- Dec 16, 2016

- 37 min read

I managed a little more controversy last time from hopeless dog owners and that’s always a laugh but I’d not reckoned on just how many people believe that keeping foxes alive is a good idea! Not so many share that sentiment about rats yet rats are landed gentry by comparison.

I have a happy little family of them at the bottom of the garden. They’ve dug themselves an underworld through the compost heap behind the turkey shed and there they play happy families, stealing food from the chickens and turkeys and gambolling playfully under the fruit trees. I have great affection for them just so long as they stay at their end of the garden, which they mostly do, though I keep their population under control with rifle and trap. They’re clean, country-living rats. Playful little things and infinitely cunning whilst doing no harm, yet if one scoots across the patio while there are any visiting women looking out of the window the shrieks can be heard from miles away. Let’s be honest here. In general, and I always say that exceptions do not disprove rules, a bloke will say, ooh, a big rat just ran across your patio while a woman will scream the place down and leap onto a chair. It’s just the way of the world.

But should a fox stroll into view it’s all, ‘Aww, how cute!’

Yes, foxes look pretty, but they really are the Devil’s instrument. Neither dog nor cat the fox embodies what’s worst in both whilst flouting the animal kingdom law of killing only what it needs to eat in favour of mass murder. Dog foxes will get amongst your flock and kill the lot, but at least have the decency to then bury them and return to feed on them later so you can shoot it when it does. But vixens just kill everything in sight, lop off their heads and leave the place looking like a suicide-bombing hen just exploded amongst them – then someone else shoots it, usually the local gamekeeper who says he’s done for about 350 of them this year without making the slightest dent in their population. As may be imagined – townies lack what’s needed to understand this… until Tiddles the cat is reduced to only his head on the lawn one morning or your twins are mauled in their beds.

That sorted the hateful creatures out – the pest controllers in London didn’t know which way to spend their money for months after that. Face reality, townies – foxes are bad to the core and best served stone dead.

Then we have dairy herds built over many years by dedicated farmers being slaughtered because badgers are infecting them with TB, (which humans don’t really want to catch) when the obvious thing to do would be to slaughter the useless badgers instead. They’re no more endangered than foxes but, no, let’s have bTB in the milk and a big hoo-ha about popping a few of them with a rifle. Look at it another way – it would drive down the cost of shaving brushes and sporrans.

The problem seems to be that the ‘save the ant’ brigade so totally believe the nonsense they’re fed that they’ve become too blind to look beyond it.

I can’t deny that it’s often a necessary tool to garner the resources needed to do any real good. When I used to dive for Greenpeace they would blatantly promote the myth that rainforests are the lungs of the world and dolphins get caught in mid-water trawl nets but it kept the cash rolling in for the stuff that does matter and that’s a difficult stance to argue with.

I was stopped in the street lately by a pretty girl bent on saving the planet by having me adopt a Snow Leopard. Telling her that it would make a splendid hat did nothing to dampen her fervour so she rattled on about the horror of fox hunting without ever questioning gassing vixens with their cubs in their den to rid the world more efficiently of an entire generation so what right did she have to whinge about giving one a sporting chance by simply outrunning a few dogs? No one I ever met who lives on or works the land ever spouted such nonsense and this dizzy, indoctrinated, do-gooder certainly didn’t tick those boxes but you’d imagine that instead she’d have enough Internet, intelligence and technology to have dug into the people she was representing and discover that it was actually an advertising agency, not a charity, that talked well-meaning folk into parting with three quid a month in exchange for some glossy pic’s and a tuppence-ha’penny cuddly toy.

Yes, they had the WWF panda logo all over their blurb but get into the small print and it turned out that it was a company owned entirely by its directors that made a tidy profit, offset the goodwill against its tax and made a ‘small’ contribution to the WWF in exchange for being able to use their logo to sucker in folk who absolutely must have a Snow Leopard.

Even the WWF – honourable charity that it is - has a couple of trading companies tucked away at the back of its effort with a healthy investment portfolio and tens of millions swilling about. Go have a dig around the Companies House website and find out for yourself that their bill for temporary staff last year was £200k and how many people are on £60k or more. Not saying they don’t do good things around the world, because they do and are worthy of respect, but precious little of your three quid ever makes it to Snow Leopard country.

On the plus side, though, for everyone with no fox experience who think the damnable things should live there were ten more who got in touch to say how they’ve ridden with the local hunt since they were nine and fully support the gamekeeper so the world hasn’t quite divested itself of all its common sense – yet.

But the one thing I detest more than ill-researched do-gooders is so-called technology that takes mankind backwards rather than forwards. Remember the car for tetraplegic morons? (Oh, by the way, I also had someone mistakenly think I was disrespecting disabled persons rather than the car. I do hope he’s not tetraplegic, that would be a double hit) Well I saw it outdone last week.

My car is due to be replaced and the model run out and supplanted next year with its prettier, younger sister so the way I see it is I’d rather have a MILF-like, reduced-price, properly sorted machine with all the toys and a final hurrah to a car I’ve liked and lived with for a few years rather than an over-priced and somewhat underdeveloped virgin years off its full potential. Of course, if you want to impress the neighbours, give a hoot what anyone thinks or can’t live without the cloud in your electronic gearbox syncing with your central heating at home you’d best rack up some debt against the latest expression of your vanity, wealth and perceived success; but if you want to save a fortune and exercise your common sense then best go for the run-out model. So this is what I was about to do until it doomed itself to death.

Now I have very strict rules about what a car should be. Firstly, it shouldn’t be any bigger than it needs to be so all those ocean liner sized, pretendy 4x4 things with massive wheels on low profile tyres are out straight away. Why would you buy fuel to haul twice as much machinery as you need around the place? Those things are just the engineering embodiment of fat people’s diabetes.

That said, those biscuit-tin sized horrors that transport your fragile feet three inches behind the plastic front bumper and promise to emit no carbon dioxides from their three cylinder, half- litre engines yet, on paper, will save you with airbags if a Range Rover whacks you at 80mph should be outlawed at once!

Nor do cars need more than two doors unless for medical reasons.

OK, old, infirm or disabled persons may struggle and need a larger car with easier access but not able-bodied grownups and certainly not those with kids. My two will happily crash into the back of a two-door coupé complete with school bags, books and coats faster than they could escape a burning building, and that is exactly what they do of a morning and why the end of line, properly worked out car I tried proved a total disaster.

We’ve all had a go on electrically adjustable stuff, I’m sure. And we know how slowly it travels – and with good reason. You don’t want your car seat or telly-facing armchair or conservatory skylight to whip over and take your head off. The ergonomic engineers of this world earn their salaries by knowing that every animal on the planet is programmed to be startled by things that move fast and soothed by things that move slowly because the former is likely to eat you whilst the latter probably wants sex; so electrically operated things are designed to glide with a whisper that wouldn’t trigger the alarms on the Crown Jewels.

So picture the scene… I’m strapped comfortably into the heated driving seat, the salesman is about to hop into the passenger side in case I go daft with his car while a pal of mine who is along for the ride is waiting to limber into the back. Except that having flipped the handle to slide the seat forward he finds that it won’t budge except by servo-operated nonsense that has all the urgency of a melting snowman. It was interminable! With an infuriating mechanical buzzing the seat inched forward like Dr. Nefario’s scooter in Despicable Me.

Yet this, according to the salesman, is better ‘because it’s electric’. It matters not a jot that our would-be back-seat passenger was gently soaking in drizzle with no means of attaining the shelter the car ought to have provided, or that the salesman was similarly placed twice over because he would be last to enter.

It was better because it was electric.

The rear seat was eventually graced with its damp recipient then the process reversed to let the salesman in about a fortnight later.

The dealership – true to form – then mailed me later to ask me what I thought. Or, put bluntly, to check out their chances of flogging me the thing, to which I responded with more or less the above. Two days later I was there for a completely different reason only to discover that, following my mail, the rest of the sales team had been for a look to see what I was on about and all agreed it was a ridiculous piece of mechanical crap.

They tell me, and I’m not kidding here either, that next year’s model has a feature whereby when you want to park, what you do is get your new car somewhere near, get out, and then using your telephone, tell the thing to park itself.

What kind of mind-boggling stupidity is that?

First of all, if you can’t park your ton of ironmongery you shouldn’t be allowed to take it onto the streets or anywhere else. I mean, can you imagine flying off on your holidays with a captain who’s hopeless at landings but he can have his jet do it on its own by means of an appamabob on his SheepPhone 7?

No…

And what to do with the wife and kids as part of this process? Fetch them out into the street before telling your telephone to move the car, in which they were safely cocooned moments earlier, potentially through the space they are now occupying? Leave them in there while you attain a safe position and hope that nothing goes wrong, or do you stay inside to be digitally emasculated by a widget when, were you any sort of a man at all, you’d be able to park your own bloody car!

Mankind is using his hard-won intelligence to make himself as stupid and lazy as he can possibly become! Those fat people on floaty chairs staring at screens in the film WALL-E are a terrifying vision of the future in my opinion!

But at least the bedrock of our engineering heritage is intact and this is why our engine of yesteryear shares much with today’s machines. The fuel pumps on modern gas turbines are still full of pistons and carbon-carbon seals. They have elastomers and o-rings and gaskets and so the time finally came to stop talking a good job and get our hybrid 701/101 spun up into some kind of action.

Our main engine is an ex-Red Arrows unit that flew with Red#1, ‘Dickie’ Duckett, in 1976. It was then used for ground-running for a while before being retired when the aircraft was overhauled. We’ve had it tucked away for years. In this shot we’ve popped the oil tank up top but there’s no fuel system on it or a starter. The starter went on first.

This is a brand-spanking new Rotax CT1009 start turbine and is meant to be used with LP air from a Palouste starting cart but we had it looked at by the engineers from Goodrich Power Systems, who inherited Rotax, and it was declared safe to run on compressed air, albeit very inefficiently – we’re working on that problem. The worry was that it has thinner casings than the HP starter so it might burst but they said it wouldn’t. Next we finished repairing the old inlet bullet.

This has been around for years too but, despite being saved whilst under the water by having a coating of magnesium hydroxide somehow deposited over it from the slowly dissolving compressor of Bluebird’s crashed engine, there was still much corrosion to be tackled and its mounting flange had different hole spacings to the 101 too. It looked OK but still took many hours of careful reworking to bring it to a condition where we’d let our precious engine breathe through it. We also had to modify it inside to clear the larger diameter starter (the 701 engine uses a CT0801 and, though we have one, it’s horribly incompatible with the 101 gearbox) and then the compatible starters we do have must be partially dismantled and the inlet clocked through ninety-degrees so we can admit air through the old 701 pipes. Just getting the starter in and the inlet on was a major undertaking. Not as major as getting the fuel system on, however…

Having decided that we’d be spending long hours under there we put the engine up on stilts and commenced our head-scratching... What we discovered quite early on was that the 101 filter bowl was held on with only three bolts though four holes were provided on the underside of the compressor casing. Next we realised that, though our 701 filter had four lugs for bolts to pass through they didn’t match the ones on the compressor – at least not all of them, but we could get three of the four (not the same three as the 101 filter, though), so this meant, in theory at least, the three it had would give us a fixing at least as strong as the different three that the 101 filter employed.

Here’s the filter bowl bolted in place. The silver thing sticking out of the left side with that downward-facing plug connector is the low fuel pressure warning switch whilst on the other side is the rigid pipe taking fuel to the piston pump, which you can just see disappearing out of shot on the right. In the middle is one of the fixing bolts, noteworthy for the small, wedge-shaped shim just visible between the filter and the compressor case.

That rigid pipe (never call them ‘solid’ pipes or someone from aerospace will get annoyed and point out that if they were solid they’d be a bar and not a pipe at all) is an extensively modified 101 part to get its angles and length correct so it went off to visit Barry Hares on several occasions until it decided to play the game. There’s another rigid pipe on the other side that delivers HP fuel from the pump to the rest of the fuel system.

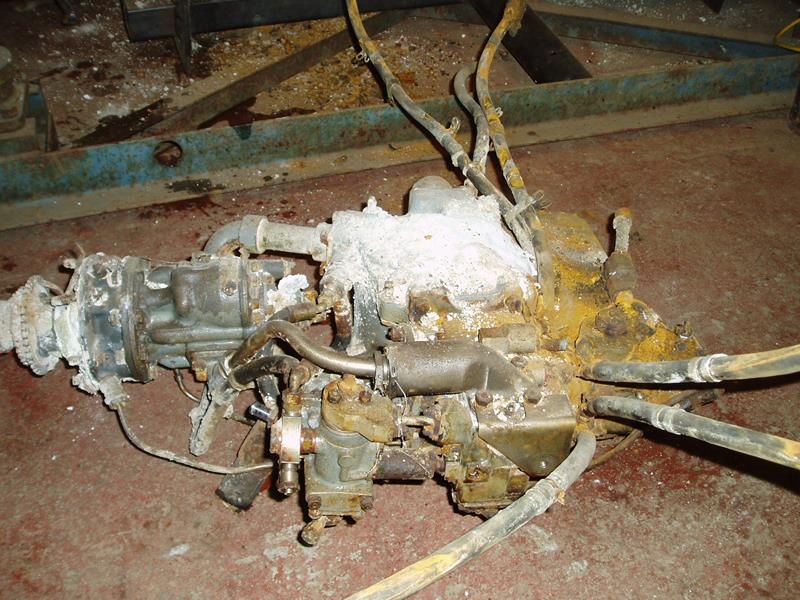

You can see it snaking away from the pump on the left and we got lucky this time because it’s another 101 part that fitted a treat once we’d swapped a few other bits and bobs over from the later engine – namely the elbow where it connects to the pump and the wire-wound filter at the other end where it meets the CCU. There’s a lot of other plumbing in place in this shot too. See that black hose coming from the bottom of the pump and disappearing into the fuel system? It delivers the all-important servo pressure to control the engine and schedule fuel on start-up. This pressure-term was to cause us no end of difficulty when trying to integrate the old 701 fuel system with the 101 engine but more of that presently. Just a quick reminder of what we started with. The fuel system was in recoverable condition because once the compressor case rotted all the gubbins dropped into the mud where it was preserved. There was also very little water ingress so kerosene looked after most of the internals. We got very lucky there – not least because of the incredible rebuild job done on it.

That was the hard part done and the rest of the plumbing was a fairly straightforward case of rinse and repeat until our engine would, in theory at least, get up and go if we added fuel, sparks and a good shot of compressed air.

Now then, by this time we had been very kindly invited to do our engine testing to full power at RAF Scampton as guests of none other than the Red Arrows! How cool is that?

But the snag was this… Absolutely no way were we going to be allowed to give it 100% until we could prove that our engine was a viable asset and that we could handle it outside of the boat – and quite right too. We’d therefore have to rig it to run in isolation and these engines don’t take easily to such treatment. They’re designed to be an integral part of an aircraft with controls and systems predisposed to operate in perfect harmony with it – not hacked out like someone’s liver then asked to keep on functioning on the slab without the rest of the body for support. What would we need?

How about… fuel?

Many moons earlier, from the depths of the mud-crusted hull, we’d dragged up this sorry looking colander of a thing.

It’s a small, six-gallon fuel tank with a submersible boost pump mounted in the bottom and, being made of 16swg steel, it was shot to Hell.

It’s there because on the Beryl engine fuel entered at the top so the fuel pipe from the tank is at the top making it a straight run but the Orph’ has all its gubbins down below so the fuel has to go all the way up inside the tank then back down to the bilges on the outside where it must then be given a positive pressure before entering the piston pump – hence the tank and boost pump.

Way too many holes to mend in this case but a small brass maker’s plate on the underside declared that it was made by a company called Gallay, which happens to still exist.

They were promptly contacted and asked if they could make a replacement and they immediately said yes – but we waited, and waited, and waited, until eventually we demanded the return of our knackered tank and made one ourselves. There was nothing to it once we got stuck in.

We salvaged as many bits and bobs as we could including the internal baffles…

All the external fittings…

And the ring where the boost pump bolts in.

Here it is ready to move fuel again, and below – as it was when we found it.

The original pump is, of course, fighting fit courtesy of Kearsley Airways and was soon bolted back from whence it once came.

Next in line was the LP fuel cock, which is mounted on another rigid pipe fabbed-up (fabricated) and gas welded by someone at Norris Bro’s back in 66 when the new engine went in. We had the original but it too was cream-crackered so it had to be replaced.

With this lot set up and pressure tested we rigged our ‘aux tank’ (as we call it) to our embryonic engine test stand in order to not only supply fuel to our thirsty Orph’ but also to test the LP pump, aux tank and fuel cock, all of which would eventually be fitted to the boat and expected to perform.

The LP cock – rebuilt by Barry Hares, having eventually been identified as a Saunders Roe part and therefore utterly beyond replacement – was operated with a 15ft Teleflex cable so we had a sporting chance of shutting it down and running like buggery if everything caught fire. But mending it proved a challenge beyond this because no sooner had Barry rebuilt it and we put fuel across it that we discovered, to our annoyance, a microscopic corrosion pore all the way through the magnesium casing. It was just enough to wet the outside of the valve and cause a slow but relentless drip. It took a complete stripdown and the application of fluorescent penetrant to find the gremlin under UV.

Mag’ is strange stuff to weld but we’d had to master this awkward little part to get it this far so another small weld was routine once the rot was drilled out – should have been a dentist.

That done, all we had to do was to spoon all these bits and bobs back inside and we’d be good for another try.

Following that minor snag the valve has been operated countless times and has worked like brand new, though the size of the aux tank would ultimately prove something of a handicap as six gallons doesn’t run an Orph’ for more than a couple of minutes but we got around that too. Back to that presently…

Next we needed sparks and to that task fell Bluebird’s original igniters rebuilt by… you guessed it. This was a great chance to test them in anger too so they were screwed to the test rig.

The only new parts you see here are the plug connectors on the red lead and the 24V connector to the igniter coils on the top. Otherwise it all saved to fight another day including the crude, grey-painted bracket surrounding the igniter can, gas-welded and filed from bits of scrap in 1966 by goodness only knows which Norris Bro’s apprentice.

The igniters were a joy from the get-go. Just switch the switch and many-plenty sparks leap around inside the engine’s delivery case to light the fire. Apart from blowing the fuse once or twice and us occasionally fouling the igniter plugs with our more out-there engine adjustments they have performed brilliantly. They have to be fairly unique as working examples too because they’re not the conventional ‘cracker’ type that discharge capacitors and deliver massive bolts of energy that will cut through any sort of contamination or wet plugs. These are a high-tension coil setup with a set of points that tremble to deliver much smaller sparks but at a high frequency. The downside of them is that it’s not difficult to foul the igniters at which point you have to take them out and give them a clean.

But it’s all for nothing if you can’t spin the engine fast enough to get it going. The principle is very basic. You turn over your gas turbine faster and faster until you get some air going through it. Next you add fuel and a spark or three until there’s a satisfying ‘whumpf’ followed by the smell of burning kerosene after which the machine whooshes up to idle speed (3650rpm in our case) then sits there howling angrily. So to give it that initial push we built a starting trolley.

Essentially a couple of hundred litres of compressed air blown to 232 bar and held back by a kit of parts that releases it on demand through a pressure regulating valve directly into the starter on the nose of the engine at 250 psi. It’s little more than a horribly violent bomb so the bottles are brand new and certified as are all the hoses. The rest is rated to 300bar so we’ve pushed the margins of safety away to acceptable values but I still have a deep-rooted fear and respect of compressed gas. All divers do…

The boat’s original start system is in full working order but we’ve imposed a max working pressure on it of 1500psi for now and that just isn’t enough for a good start. In the meantime we’ve converted an LP start turbine to run on HP air by copying the internal features of the HP starter and done some testing and it’s showing great promise but it’s not been tested in anger yet.

From here all we needed was a smattering of instrumentation and a means to control the LP and HP valves…

We popped a pair of thermocouples into the jetpipe (see those shiny tubes poking inwards at the 10 and 4 o’clock positions?) – new ones copied from the old ones by you know who. They’re K-type, Chromel/Alumel thermocouples that use dissimilar metals to output a few millivolts as they heat up that then powers an indicator to tell what’s occurring at the hot end. At 580C (our target JPT at idle) they output 24.05mV. Not a penny more, not a penny less. Clever things, thermocouples…

Easy to test too – all you do is poke your head up the jetpipe, blowtorch in hand, heat them up then scoot around to the instrument to see what’s going on. And if you need to calibrate them you can boil them up in a pan of water to get 100C and adjust the indicator to suit.

You can just see the tacho indicator here too on the right… It’s also a very simple system. A 3-phase generator driven by the engine gearbox runs in phase with a 3-phase motor inside the indicator that then drags a magnetic induction cup around to indicate RPM. It’s all a little crude but good enough for what we need.

But here’s an interesting fact. The indicator wasn’t matched to the generator in our day or Donald’s because the indicator reads from zero to 12,000rpm (and it’s an identical model to that fitted in 66/67) whilst the generator produces a value from zero to 10,000 rpm so without the clever re-calibration carried out by – yes, you got it again – it would always read low, which seems to have caught out our Donald all those years ago if anecdotal tales of the engine not giving it’s all are subjected to a little bit of reading between the lines. We’ve fixed all that, though. Now all we needed was a means to control the throttle and LP cock and we’d be good to go. So we built a quick and easy pair of control levers…

A smattering of bearings and ground-shafting, some leftovers from the sponsons and a couple of Land-Rover throttle knobs and we had all we needed to push and pull the Teleflexes to our hearts’ content with an accuracy of a few thousandths of an inch. All we had to do was push the go-button and our engine would light in an instant and howl its appreciation just as we imagined. We wheeled our ‘engine on life-support’ out into the spotlessly fodded yard, coupled up the air and instruments, added kerosene then, in a buzz of excitement, whirring pumps and crackling igniters we opened the taps and hit the starter.

With an explosion of compressed air the starter screamed and the engine spooled up eagerly. There followed the expected whumpf of ignition followed by the smell of burning kero’ blasting through a shimmering haze of hot gas exiting the jetpipe – then it all bogged down and got very hot whilst failing completely to accelerate until we had to shut it down.

Now here’s the oddest thing. Rolls-Royce, or Bristol, made the engine but not its fuel control system. That was made by Lucas Gas Turbine Equipment but they had nothing to do with the engine itself.

But what’s really peculiar is that where the two meet is all theoretical with flow rates and graphs and figures swapped back and forth so the air is right for the fuel and the fuel is right for the air and each does their thing such that when all the bits are bolted together they just do what’s expected and the engine works a treat.

That is until you make a half 101/701 Frankenstein’s monster then try to make it live and breathe with the rebuilt heart of a 1959 test engine bolted to the underside of a much later engine. Somewhere along this very non-aerospace path something went wrong. The engine just wasn’t going to go and, most amazingly, no one knew how to fix it. We had the very best of the best experts from both engine and fuel system camps moving Heaven and Earth to work out what the trouble might be but the nebulous no-man’s-land of where fuel system meets gas turbine seemed not to have an expert we could turn to. We were going to have to work this one out ourselves.

I must point out here that we had no right to expect any support whatsoever from aerospace yet we were extraordinarily privileged to receive it nonetheless but we were operating so far beyond their remit that it’s hardly surprisingly that we all ended up bamboozled. That said, to their immense credit, they stuck with us through thick and thin so personal thanks are due to Andy Hilton, Nev Pettifer, Stuart Baker, Tom White and Ade Mason plus all the others behind the scenes who looked out for us.

So, back to the tale…

Cutting a long and painful story short, after some 300 starts we finally learned to properly handle our hybrid Orph’ and understand its fuel system and how to set it up. Where it seems the problem lay is in the way the main fuel pump – an early and quickly superseded model (but, crucially, the mud-covered example we lifted out of 140ft of water) – develops its servo pressure, which controls fuel-scheduling on start-up and then pretty much everything else. The later pumps make this control pressure almost as soon as they begin turning but ours creeps up on the problem with painful slowness and as the factory-testing of our fuel system used procedures beginning around 500rpm at the pump the values below this were a little unknown. It wouldn’t have mattered with the later pump but ours just couldn’t climb over the top quickly enough so our engine overheated and bogged down time and again until we realised we had to relax a setting or two elsewhere to allow it to wake up gradually. Once we bottomed that problem our engine would leap into life at the push of a button but it took several intense months of experiment, frayed tempers and finding the will to do it all again day after day to get there.

We spent countless hours adjusting, tuning and tweaking until our engine would light at the prescribed three seconds then scream its way to idle at 3650rpm yet, no matter what we tried, it never did it in the prescribed seventeen seconds that the later pumps can manage. We would later prove this out by lighting our second engine whilst instrumenting its various pressures and that one did make it to idle in 17 seconds.

Then, with it all working, we added our new inlet trunk (more of that in a mo) and inlets to put a test on those too.

We worked like a F1 pit-crew every evening after work to wheel the rig into the yard, attach the instruments and controls, fetch fire extinguishers, fuel, compressed air, Mike’s ‘aerospace data-acquisition table’ (oft-mistaken for an ironing board by the uneducated), and chairs before cramming in as many engine runs as possible until we’d learned our fuel system so well that we could predict with deadly accuracy what effect every tweak of an adjuster would have.

One of the biggest drawbacks we had once the engine was up and running was the short duration on only the aux-tank so to get around this we rigged a 45 gallon drum. This took our duration up to about 20 mins.

A hard-won and excellent result but next we had to get it into the boat and make it work in there as a self-contained machine. Actually craning it in is a doddle. In the final instance we finished our engine test, forked the rig around to the main workshop and the engine was still warm by the time we got it into the hull. This was the occasion we were joined by a new team member- introducing Stew Campbell-

From our engineering association with the Red Arrows came word that one of their pilots- Red 8, as it happens- was very interested in the project, and as we have Ted who knows about boats but not necessarily jet engines, and now Stew who knows about jets but not boats, it seemed like a win-win deal to invite Stew on board as Driver No.2 so they can learn from each other. Stew grew up hearing about his famous namesake and at the time of writing, he’s just finished his three year stint with the Reds; we’ve no doubt he’ll be a true asset to the team.

Getting the engine back into the hull was only part of the story because before it would run in there it needed all its various systems connected up and one of the first was the inlet trunk that connects the inlets to the engine. The inlets were designed around the old Beryl so a long, tapering trunk was made in 66 to adapt them to the mouth of the Orph’ and it was a bit broken.

It had gotten itself into an electrolytic battle with the steel start-frame above and come off second best. If we mended this one it would be more patch than original with the added joy that we might miss something that would later let go and FOD our precious engine. It just wasn’t worth the risk. Besides, there was another problem. See the rugby-ball-shaped indent at upper right – designed to clear the underside of the left-hand start bottle… now notice how it’s partly under the curved angle at its right-hand edge? Well it shouldn’t do that and the reason it does is because, annoyingly, the Orph’ 101 is 38mm longer than the old 701, which may as well have been a yard and a half from our point of view when it came time to package the engine. In the above shot we’ve removed the angle, cut 38mm off the right hand side of the original trunk then put the whole lot in the hole to get a look at the sizes and shapes we needed to make a new one.

Worse still, the trunk is not just a straight tube.

Whereas its top surface is parallel with the deck of the boat the lower surface slopes downwards towards the floor because the diameter at the inlets is greater than that at the engine but the heights of the top of the engine and top of the inlets is the same. We built a new one from scratch.

But we did save what we could of the old one, namely the attachment angles that run down the sides and the semi-circular ones that press on the rubber seal around the front of the engine; but mostly the old one was retired. The angles were originally gas welded to the trunk so the heat distortion must have been horrendous. We couldn’t judge it because the crash damage was far worse but we chose to rivet the parts on this time to hang onto the shapes.

Another irritating problem was that the longer engine also got in the way of the start frame, which needed relieving a little to clear the engine inlet and all the fixings at the bottom of the trunk that secure it to the hull had to be redesigned, again using as much as could be saved from the original parts.

We also saved most of the control runs.

There are three rods running aft to control the engine. Two slide and operate in both compression and tension whilst the third rotates to open and close the LP cock.

Of the first two, one of them is operated by the Bloctube control to open the engine fuel valve 30 degrees for starting and the other is attached to the foot throttle to provide the remaining 60 degrees for going fast. They were all chopped off around F-15 in the crash but we later recovered many parts from up in the cockpit so the only new in them is the short sections where the damage was worst. They work a treat.

But then we had to revisit the fuel system, because there’s quite a bit more of it then we included on the test rig and it too had to be incorporated into the hull, tested and then asked to function just as in the good old days.

There was, for instance, the main tank, mostly emptied of fuel then crushed by water pressure as it sank, captive within the plummeting hull.

It’s made of the softest, most buttery alloy imaginable. Below is how it looked in November 1954 when fresh off the tools.

Pretty good for having been gas welded but by the time we took delivery there was a lot of stretch and a fair amount of corrosion to tackle – so we asked a favour of our old mate, Chris from Proalloy who, as we knew he would, rose to the challenge and soon they had a kit of parts..

Their workmanship is the dog’s thingamy-thangs, it really is, so they had the tank expertly mended in no time flat.

An interesting shot showing the tank’s interior. At the top you can see the hole for the filler cap to the left of which is a small pipe coming down from the roof of the tank and exiting into the left-hand external fitting as you look from this side. That’s the breather and it’s plumbed externally to that small pipe that sticks up from the top of the air intakes near the aft edge where intakes meet engine cover. The down-coming pipe to the right of the filler is the main pickup for the fuel and extends to within an inch of the bottom of the tank. We asked Chris to install a larger diameter pipe as the original was for the Beryl and smaller in diameter than the Orph’ fuel lines. Once closed up and welded the tank looked exactly like itself and we’re most grateful to Chris and everyone at Proalloy for all their skilful work in mending it.

Yet, even at this stage, the fuel system was incomplete because those well-versed in Campbell lore will tell you that things just weren’t happening in the engine/fuel dept. in late 66, a problem finally bottomed by the installation of a second boost pump. Having installed said pump the immediate result was masses of power followed by a terrible accident so the pump installation was (we believe at this time) never photographed. We were therefore intrigued to discover this thing under the covers clashed into the position formerly occupied by the in-line fuel filter.

See upper-left that vertical cylinder bolted the bulkhead? It’s a one gallon tank with a boost pump in the bottom. You can see where the outlet pipe has been taken off and the electrical connection is still made with its wire trailing downwards. On the upper face you can see the remains of the hose from the main tank (left) down to the ‘swirl pot’, as we call this thing, and a blank (right) that we believe was for filling the lower half of the system including the engine filter and the aux tank. It was built using pieces of old battleship, weighs a ton and repaired effortlessly by the simple expedient of wrapping a new outer skin around the cylinder and brazing it in place.

All mended and painted with the rebuilt pump in place and its hoses tightened up. We’ve no idea what colour it or the aux-tank are supposed to be – assuming they were ever painted in the first place.

The aux-tank, most likely, it went in at Burrell Road but the swirl pot might never have been painted, especially considering the heaviness of its construction and the hurried nature of its fabrication and installation. We decided to paint them both black for now. 34 years underwater and all it suffered was a few small holes. Notice also the hose that leads up to the main tank, in particular that short, steel section with a strange looking block attached to the top. Here it is again, part built.

On the right is the breather – all original except for the piece of period garden hose – and on the left is the main fuel line complete with metal block and a strange, stainless steel valve poking vertically off the end of it. Now go to your archive pic’s of the Orph’-engined K7 and find that part – bet you’d never noticed it before. Both the block and the valve are original and what it’s for is to let air out of the siphon in the main fuel line. It’s situated right at the very top so you can either brim the tank and operate the valve by pushing down on its top or part-fill the tank and suck the air out.

This we did and with the siphon purged and both pumps running we saw exactly what we expected to see – near enough 20psi LP boost pressure before our Orph’ hopefully sucked out the bubbles. Great news at the time but this seeming triumph was to create yet another gotcha. Back to that soon.

By now we had a pretty much complete machine with all her systems in place, mostly tested and ready to go. Next we had to get the whole shooting match out of the workshop and around to the yard so we could fire her up and this meant more mod’s to our long-suffering but ever-loyal recovery cradle. This time we added a central axle with a pair of super-strong tyres on original Minilites and a 350kg-rated jockey wheel at each corner. We like to keep such arrangements to a minimum of both engineering effort and cost as we reckon on using them only a handful of times so we built what we thought would do the job and gave it all a push…

Now this was properly weird… You see, in the workshop it’s impossible to get this far away at this angle so we’d never seen her like this and she was very impressive. First thing many people asked was why she was so stripped back – well think about it. If we were going to have a fire or an explosion where’s the sense in exposing more than absolutely necessary of all our hard work to the flames? This was just a test to see if we could handle the boat then get her back inside, and we managed it fairly well – the actual engine run was scheduled for the following Saturday when the forecast was shocking.

On the appointed day we pushed and pulled and manoeuvred with the additional manpower of Novie, Sir Malcolm Pittwood and Paul Hannarak fresh from Records Week. Other visiting dignitaries included our old ally Gerry Jackson from BBC Newcastle who has looked after us so well on so many occasions. Ever loyal to our title sponsor, Sky News, I made the calls but they were all on the other side of the pond in pursuit of the wrong Donald so we were given a buy to work with our Beeb mates once again.

The weather held for just long enough to lull us into a false sense of security… We carried out our preparations indoors with the door open and welcoming skies outside. Our engine had been inhibited some time earlier with Aeroshell #1, the same stuff they pumped through the Vulcan’s Oly’s. It’s expensive juice that keeps today’s modern, sulphur-contaminated fuel away from the delicate, silvered components in yesteryear’s fuel systems. Back in the day the sulphur was removed because silver was the only answer but once carbon came along and the silver went the journey the sulphur was no longer a problem and its costly removal unnecessary. That said, most of our engine testing was done with de-odorized kerosene and the way the stink is shifted is to take the sulphur out. It’s horribly expensive but a worthwhile precaution.

But now we had to get her veins filled back up with kerosene so we filled the aux-tank, fired up the boost pump and spun the engine on the starter with the throttle valve open until we got fuel in the engine drains – we thought that would be plenty. It’s an odd situation. You open the taps, spin the engine and the juice disappears inside just as expected. But it doesn’t come back out, so you put some more in and try again and still it eats it and hangs ono it. It tends to be on the third occasion that pretty much everything you put in comes gushing back out and the drains are overwhelmed. Where does it go?

Never mind… we did this and concluded we’d done enough to get the engine ready to run so we wheeled the boat around to the main yard and got her ready. On the left you can see the start trolley rigged to the engine and, if you look a little closer, you can also see the ratchet straps tying the boat to the cradle, not to mention the jockey wheels wound down solidly onto wooden kickers to keep her from moving. We later saw some movement amongst them on the video footage and the bolts holding the jockey wheels all had badly stretched washers when we were finished so our little Orph’ was certainly pushing hard.

On the right is the untried fuelling arrangement consisting of a forklift, a couple of drums of kero’, a palette or two and a trio of puzzled blokes. The heavens opened just as they worked it out.

Here, John tips in the last of this drum having sat up there interminably while the fuel trickled downwards in time with the heavenly deluge. We felt it important to absolutely brim the tank on this occasion to check for leaks and to maximise our chances of purging the siphon – stupid arrangement that it is. Why they didn’t put a fix on the tank at the same time as mending the imploded inlets we will never know; seeing as the tank had to come out to get the inlets free in the first place.

All they had to do was let a bulkhead fitting into the tank low down to feed the aux-tank or, better still, fit a boost pump to the tank itself while it was all in bits, giving them a fair chance of dispensing with both the aux-tank and the swirl pot – but they missed that one for some reason.

Never mind… John brimmed the tank… It took about eight gallons to fill the filter, aux-tank and swirl pot with their associated hoses and the main tank holds 46 gallons so we crammed a drum and bit in there – and not a drop of it leaked out.

…first time in half a century, and we were ready to go.

Now what should have happened is this. With the LP cock open and the HP cracked to 30 degrees for starting (the linkages had been set up to a nicety for this very purpose) the igniters would provide sparks so when the start button was pushed and the whooshing began the engine would light in three seconds and the JPT would begin to climb. Wait for 300 degrees indicated then come out of the starter and watch the tacho-indicator and JPT as the engine spins up to idle. Simple as that. That is what we’d grown accustomed to over the summer so there was no reason to think it would be any different this time.

All of the above went to plan except that three seconds came and went without a hint of ignition. At six seconds the starter was disengaged and the engine began to spool down disappointingly. What had gone wrong? And then, whumpf! It lit on the way down – never a good sign. The engine should produce a combustible mixture on the way up. In our experience, doing it the other way is a sure sign of over fuelling. The resultant fireball in this case was very impressive, though totally useless!

As is always the case with the engine lighting on the way down, indications from the instruments were of rapidly rising JPT and almost no acceleration of the engine so, based on instruments alone, as the fire was invisible from the cockpit, the engine was shut down with a JPT approaching 700 degrees. It spooled down normally but a lingering fire in the combustion chamber necessitated a couple of blasts with a CO2 extinguisher and the blanks applied to extinguish it. The man from the telly thought it was great – well he would – but when asked whether he’d be happy to remain on the flight if one of the engines did that as he was about to fly off on his hol’s he was a little hesitant.

Not a great start but it was soon attributed to perhaps not properly flushing out the inhibiting fluid and therefore the engine being halfway through its start procedure before getting a lungful of burnable kero’; but by then it was going too fast to light. So it lit on the way down instead when the place was awash with spare fuel and inhibiting fluid so we just got a bonfire. Hmmm – we decided we’d best try again.

We had a debrief, as we always do after an engine run, and then prepared for our next attempt. This time, surely, we’d get a combustible mix on the way up and she’d go. Not a chance. Instead we got a cloud of kero’ mist (another giveaway when over fuelling is the culprit), another light on the way down and another shutdown due to soaring JPT.

This time we knew it wasn’t inhibiting fluid but what the hell was causing this latest problem with an engine we’d run over 300 times? Having failed on our next attempt with similar results followed by a total failure to light when we tried yet again, which we soon traced to a popped fuse in the igniter circuit, we put the start bottles on charge and set about removing and cleaning the igniters in the rain…

…an operation only made possible by the amazing dexterity of our mate Dave who is a mechanic with the AA and oft admired by the ladies on our team, then we sat and had another meeting to ponder what variety of bloody-annoying gremlin was thwarting us this time!

It was Mike who first suggested that the elevated LP might be the culprit – but surely not…

Our boost pressure had gone from 10 to 20psi whilst the servo pressure at idle was about 80bar.

By the way – a quick digression about units... When I was a kid they tried to teach me metres and all that other metric stuff, but with decidedly limited success because my first year in school was when the world went decimal and the teachers were as puzzled as the kids. Then the family was in the building trade so I came up with old tradesmen who worked resolutely in feet and inches until they died so I’ve used them ever since because I reckon the old units are much safer than the new ones. Let me explain – 100ft of water sounds deeper than 33m so you watch what you’re doing down there, 80 degrees Fahrenheit sounds hotter than 32 degrees C and 232bar doesn’t sound half as blow your head off-ish as 3300psi. Safer, you see. Besides, metres, kilometres and all that other silliness was only invented to dumb down the system for those who can’t do fractions or count to twelve. And when would you ever say.

“I’m just nipping down to the local for a swift seventy-five centilitres, Pet…”

Anyway, surely our higher LP value couldn’t affect the engine starting – or could it? Servo pressure is everything, it controls everything, it pulses through the veins of the engine’s fuel system pushing on pistons and diaphragms, sitting poised behind valves waiting to be released and exerting its influence on every aspect of controlling the engine. But it’s generated mechanically inside the piston pump so its initial value is zero so, knowing our fuel system as we do, we began to wonder. How it works is that a set of burners in the engine is immediately supplied with fuel soon as the piston pump turns with no stroke on it just to light the fire then, almost immediately, another piston is forced down a ported sleeve extending a spring as it goes in what’s called the ‘pressurising valve’ opening port after port as it runs ahead of the increasing fuel delivery pressure as determined by the increasing servo pressure. It’s this that schedules fuel on start-up allowing the engine to accelerate smoothly whilst maintaining optimum mass-airflow for cooling and combustion without over-temping the turbine. Except that our poor little pump really struggles to make servo pressure right down in the weeds so to get around this we’d taken almost all the spring pressure off the pressurising valve to get it moving early-on. Could the increased LP pressure, albeit only an extra 10psi, have that much influence amongst the lower values on start-up? We surmised that the whole system had to pass through 10psi on its way to 80bar so maybe there was a point at which these seemingly low numbers became critical. Easy way to find out – we just unplugged the pump in the swirl pot and dropped the LP back to 10psi – and guess what…

The effect was immediate and electrifying!

After so many test runs on our rig the engine has a certain feel. Holding the starter in for just the right length of time became intuitive as did the subtle adjustments for the first, cold start of the day then the subsequent hot ones.

The Orph’ rebuild manual says the following on the subject.

‘Considerable experience is required before the exact moment to terminate the air supply can be determined.’

We had all that down but in the unfamiliar confines of the cockpit with it all going wrong everything seemed new and untried. But when it finally lit on three seconds the situation switched in a heartbeat from frustration in the rain to much excitement. The bloody thing had sprung into life! The engine accelerated this time tearing madly at the air either side of the cockpit with JPT stabilising at a very acceptable level. Up it went to idle but then began to decay again. Suspecting that maybe the siphon hadn’t worked and the engine was about to drain the aux-tank and swirl pot then flame out it was given a bootful of throttle and with a pained howl it accelerated once again then settled at idle having sucked out the remaining bubbles from the fuel. The JPT also remained well under what we’d seen in the summer because of the colder ambient temperature and so much water in the air so we made another discovery – our AFRC was spilling properly.

The Air Fuel Ratio Controller watches the pressures at either end of the compressor to keep the engine from surging. Without it the sudden slug of fuel thrown into the combustion end if the throttle is slammed open would cause the pressure in there to exceed the pressure in the compressor and the hot gases would vomit from the wrong end – it’s called a surge. The AFRC spills servo pressure causing the piston pump to de-stroke until the engine catches up at which point it restores the servo pressure and off you go. But we’d never managed to get ours set up so it wouldn’t over-temp the engine on slam-accelerations. We’ll sort it out on the next round of engine work but it wasn’t going to affect our in-hull testing so we let it go for now. But with the lower ambient temperatures it spilled hard enough to allow some full-on slam-accelerations and the resultant induction roar was truly magnificent. There’s some colour footage of the boat setting off in the documentary, The Price of a Record in which the exact same roar can be heard – it’s eerie.

We ran the engine for only a few minutes then made sure it would shut down properly during which a strip of rubber from the cockpit rail almost became detached and went down the engine. That would have been the end of our engine and much heartbreak would have ensued – you really have to be careful with these things, it would be so easy to break one.

We removed both rubber strips for safety. The second run was more controlled and lasted longer as the engine was slowly stepped up to 65%. It had plenty left to give but things were beginning to move around, not to mention the dramatic effect on guttering, roller shutter doors and letterboxes, so we wound it back to idle then shut it down again. Ted took the controls for the third and longest run of the day to get a feel for everything then that was our engine running complete. Putting the boat back in the workshop was no drama, though everything and everyone was soaking and darkness was falling rapidly.

Next job was to gut the hull back to bare bones, get her on the rollover jig once more and resume the fabrication work to get her outer skins and floors fitted. One thing of note is that the dreaded siphon remained intact from the Saturday to the following Wednesday when we de-fuelled the boat by simply closing the LP cock, removing the hose to the engine and fitting a longer one to a drum, then switching on both boost pumps. They emptied the tank in seconds.

So now we’re on the last big push to get the main hull all buttoned up and watertight but what’s most exciting is that, though the boat is back in bits, pretty much all of those bits are now made, tested and working and take no time at all to bolt back together. We now have to fit the outer skins and install the floors – the main outer floors being the last big challenge. Something to keep us busy over the winter.

As the saying goes… if you don’t give in you can’t fail and twenty years on we’ve yet to give in.

Comments